John: Well, Crotona Commune had these old heads, like nationalists and commies, who were always showing up everywhere and always talking about how we should all work together. They had these, I do not know, agendas? Platforms? Ideas of how things should work in the future? The dance scene I was in initially had none of that. We just took care of each other and believed in that. …By 2050 you would start hearing like young thugs and tweakers repeating something they had heard a commie from the Crotona Commune say, like they were really thinking about it. I was kind of one of those kids too. .. But I’d also argue with them.

— Everything for Everyone, An Oral History of the New York Commune 2052-2072, M. E. O’Brien, & Eman Abdelhadi, 2022, Common Notions

Food and employment for people in rural areas – where most of the world’s hunger is concentrated – remains unaddressed. Hunger becomes politically significant only when the poor come to the cities and turn it into anger, and when there is a threat of an uprising to challenge the laws of cheap nature. Here, in the bourgeoisie’s interest in this law and in its need to keep the workers quiet, we find the origin of what has come to be known as the Green Revolution.

— A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things: A Guide to Capitalism, Nature, and the Future of the Planet, Rajeev Charles Patel & Jason W. Moore, 2020, Verso

The confrontation of “we!” versus “them!” is not created by the mass media controlled by the powerful, but by algorithms controlled by the powerful, which, thanks to identity politics and the misuse of technology, supply us with new groups of “them!”. Problems and solutions are pre-determined and fed as hook bait to the hungry, who on the one hand are standing against each other, but at the same time are together on a sinking ship,

“us-and-them”.

The actual Paul Freire’s oppressor, has successfully made himself invisible. He is everywhere and nowhere just like the Big Three, who control ninety percent of the Standard & Poor’s 500 companies, including those investing in the nuclear weapons industry. Immersing oneself in an exploration of who the real “they” are, depends on free time, finances, health, luck, skin color, gender, age or family and social background. Such immersions rarely occur in schools, where the spaces of exploration are occupied by the very isolated spaces of identities, at best, and at worst, by an agenda for competitive individualism designed to ensure that the graduate will have a better life than the others.

However, surviving the pandemic period, although differently by different social groups, has shown new possibilities and developed imaginations about possible futures (think of the falling emissions curve or the expropriation petitions, for example) and our abilities to change the trend set by the oppressors.

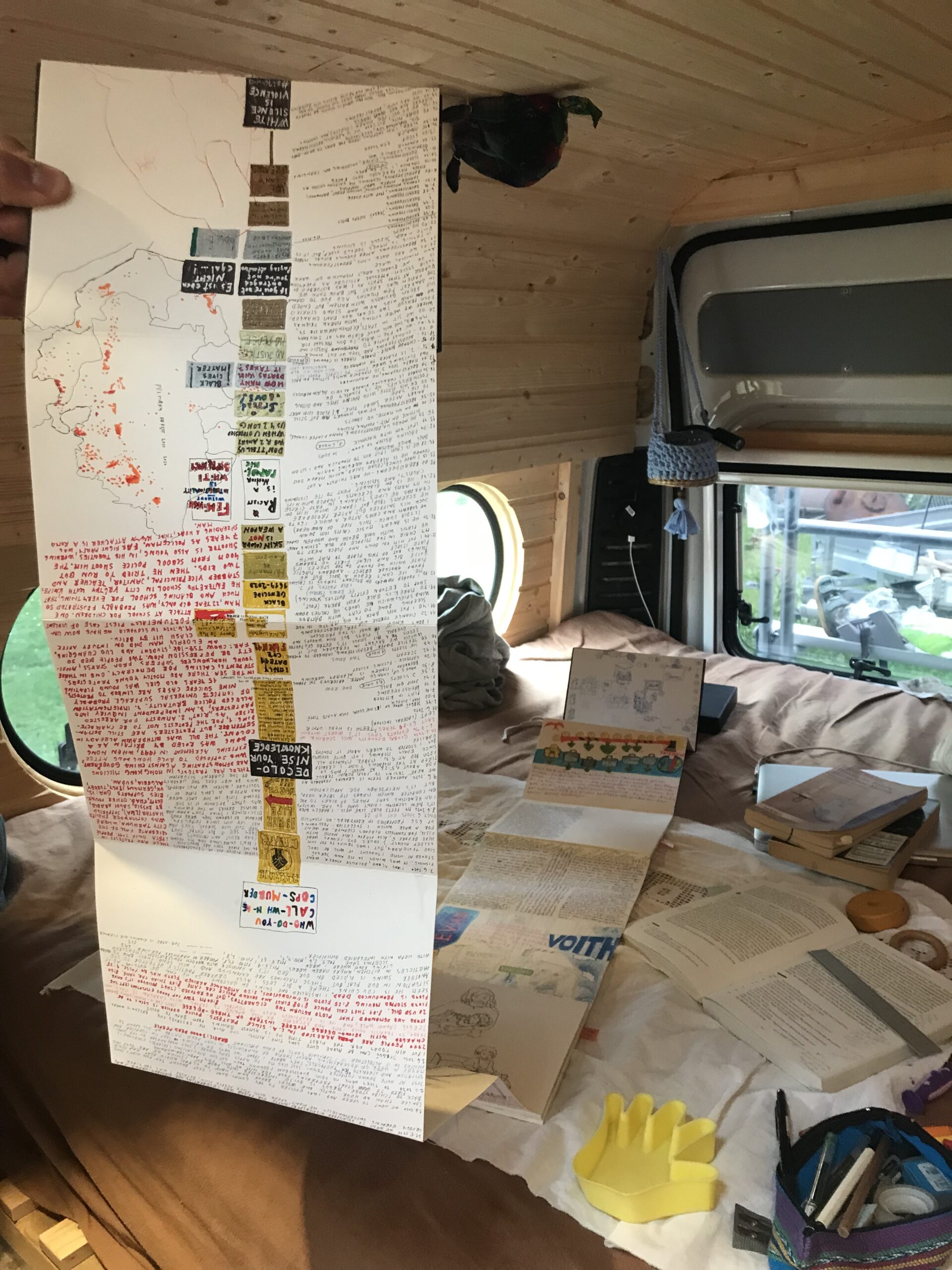

The timeline passes through three bodies drawn in pots: my body 1981 – 2040, my grandmother’s body 1921 – 1980, and her grandmother’s body 1860 – 1920. It traces the trend of the crisis from managed to unmanaged capitalism and the ecological catastrophe associated with it.

The author reflects on the role of the artist-researcher who presents unreadable knowledge. She tries to account for how many lives have to be paid for her own research, because education is freedom, but at the same time this freedom is built on the bones of others.

Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version)

Supported using public funding from the Slovak Arts Council.